Julien Dupré, A Naturalist Painter

Janet Whitmore

I. Setting the Stage

Writing to his brother Théo from The Hague on a Sunday afternoon in December, Vincent van Gogh expressed his enthusiasm for a painter whose work had captured his attention. “Do you know whose work has made a deep impression on me? I saw reproductions of Juilen Dupré. One was of two reapers, the other, a splendid large woodcut from Monde illustré, of a peasant woman taking a cow into the meadow. It seemed to me outstanding, very energetic and very true to life.”[1] Although the exact identity of these two paintings is uncertain, van Gogh’s admiration of Dupré’s work illuminates a theme that permeates European art during the second half of the nineteenth century—rural life and the work of agricultural laborers.[2]

This theme has its roots in the genre paintings of sixteenth century Dutch and Flemish artists such as Pieter Bruegel (1525-1569), but it is not until the middle of the nineteenth century that it emerges as part of the Realist challenge to the French academic tradition that categorized such imagery as being of less importance than history painting, religious painting and portraiture. The painters who lived near the village of Barbizon were among the first to declare rural imagery worthy of serious consideration at the Salon; and although they did not have much success persuading the Salon juries to share their perspective, they did attract the attention of colleagues in other parts of Europe.[3]

Fueling the Barbizon painters’ advocacy for rural subject matter was a growing concern about the destruction of the natural environment in the wake of industrialization. Not only was the countryside being carved up by railway lines and steam-powered factories, but the need for vast quantities of natural resources resulted in deforestation, in the creation of unhealthy, unsafe mining practices, and above all, in the denigration of the people who worked under these conditions. Further, as people increasingly sought factory jobs in the city, the countryside saw a significant population decline. These social and economic developments disrupted the agricultural rhythms that had been the foundation of life for centuries.

The aesthetic response to these new conditions was both stylistic and political. The Revolution of 1830 in France prompted an interest in depicting the daily life of ordinary people, often in the context of the social issues of the time. The influx of people seeking work in the new industrial economy of Paris resulted in new pressures on both social service providers and the city’s infrastructure. The effect was all too predictable—poverty, unemployment and illness.

fig. 1. Philippe-Auguste Jeanron, Scène de Paris, 1833. Musée de Chartres, Chartres, France

The arts community reacted in many ways. Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) worked for La Caricature and later Le Charivari, both journals established by Charles Philipon in the 1830s, where he created satirical images lampooning the corrupt and incompetent government as well as self-important public figures. The painter Philippe-Auguste Jeanron (1809-1877) expressed his dismay through canvases depicting the plight of destitute families. In the painting Scène de Paris (1833), the poverty-stricken family of a war veteran sits huddled against the quayside wall while well-dressed Parisians stroll past without a glance. (fig. 1) The artist’s traditional training is evident in the composition and the handling of space as well as the figures, but the subject matter represents something quite different from earlier genre paintings. These are not amusing peasants, nor do they offer a picturesque glimpse of a Dutch kitchen or a French sitting room. Rather, this is a contemporary Parisian family whose father served in the military, but whose fortunes are dismal; they are hungry, tired and ill.

Although Romantic painters often expressed political views unapologetically, Daumier and Jeanron were among the earliest artists to reveal their social concerns without the mediation of literary, allegorical or historical iconography.[4] In his commentary on the Salon of 1833 the art critic Gabriel Laviron (1806-1849) was one of the first to call for an art that focused on the contemporary life of Paris, renouncing the coded allegories of the academy in favor of a more unvarnished portrayal of real people and activities. “Art does not consist of making trompe-l’oeil [imagery] but also of creating the specific character of each thing that one wants to depict. To do that, one must see and understand, so to speak, that it is necessary to have a spirit strong enough to grasp the characteristic differences that are in nature, and what is perhaps even more rare, the audacity to show them in all their truth.”[5] By the end of the 1830s, a new aesthetic based on contemporary life had emerged. Although not yet labeled as Realists, these artists accepted the traditional techniques of painting while simultaneously rejecting the convention of conveying meaning primarily through classical allusions and historical references.

By the time that Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) arrived in Paris in 1839, the core principles of the Realist movement were already in place, but the young painter from Ornans would quickly make his presence known. He spent hours copying sixteenth and seventeenth century masters in museums, and in 1844 he began to exhibit at the Salon. Courbet gradually developed friendships with the art critics and writers Charles Baudelaire, Max Buchon and Champfleury as well as the painters François Bonvin, Armand Gautier and Jean Gigoux. The group often gathered at the Brasserie Andler on the rue Hautefeuille to ponder the definition of Realism while consuming what was then a new addition to the menu of Parisian cafes—beer.[6]

These discussions would be interrupted with the outbreak of revolution in February 1848. The corruption of Louis-Philippe’s government had become intolerable, and the disenfranchisement of working and middle-class citizens resulted in deepening support for reform. Because the government prohibited public demonstrations, the leaders of the reform movement implemented a strategy of hosting large banquets suitable for both fundraising and discussions of the issues. When the government outlawed the banquets in February 1848, Parisians took to the streets.

One witness to these events was the English journalist, Percy Bolingbroke St. John (1821-1889) who described the view from his window on February 22, 1848.

At this very time [about three], having returned to my residence to write a letter, I was witness to a scene, which described minutely, may give an idea of many similar events. My residence is situated in the Rue St. Honore.... Called to my window by a noise, I saw several persons standing at the horses' heads of an omnibus. The driver whipped and tried to drive on. The people insisted. At length, several policemen in plain clothes interfered, and as the party of the people was small, disengaged the omnibus, ordered the passengers to get out, and sent the vehicle home amid the hootings of the mob. A few minutes later, a cart full of stones and gravel came up. A number of boys seized it, undid the harness, and it was placed instantly in the middle of the street, amid loud cheering. A brewer's dray and hackney cab were in brief space of time added, and the barricade was made. The passers-by continued to move along with the most perfect indifference...[7]

fig. 2. Thibault, (1830-1927), Barricades rue Saint-Maur. Avant l'attaque, 25 juin 1848. Daguerréotype. Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The revolution concluded on February 23 when Prime Minister Guizot resigned and King Louis-Philippe fled to England in disguise. A provisional government was formed under the presidency of the poet Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869). The Second Republic was declared on February 26; universal male suffrage was proclaimed on March 2; and elections were scheduled for April 23. Peace was short-lived. By June conflict between the progressive and conservative wings of the new government ignited another revolt by the working class citizens of Paris. Barricades were again erected in the streets and the army and national guard were called out to extinguish the uprising. (fig. 2) Ultimately, the conservatives won with the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte in December 1848. Almost exactly three years later, Louis-Napoléon staged a coup d’état and dissolved the National Assembly, thus initiating the Second Empire.

Despite the social and political tumult of the Second Republic, it provided a welcome respite from entrenched academic juries favoring the status quo in art. The Salon of 1848, which opened a scant fortnight after the revolution, was open to all artists and there were no juries. Understandably, it was somewhat disorganized and overwhelming, but it did presage a more open-minded attitude toward the annual selection process. The following year, the Salon featured a variety of painters who would be identified with the Realist movement, including Rosa Bonheur, François Bonvin, Honoré Daumier, Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau. Above all, this Salon signaled that Realist art was increasingly accepted among the Paris arts community.

The Salons of 1850-51 were combined, opening officially on December 30, 1850 but not to the general public until January 3, 1851. This Salon was dominated by several controversial contributions, including Courbet’s The Burial at Ornans and The Stonebreakers, as well as an equally problematic painting by Millet, The Sower. These canvases challenged public notions about rural life, provoking discomfort among viewers and critics alike. The Burial at Ornans depicted a funeral service attended by villagers who bear many signs of fundamentally unattractive human frailty and suffering; and The Stonebreakers and The Sower reminded viewers that these anonymous laborers engaged in onerous work to ensure the survival and comfort of bourgeois Parisians. They break stones to pave carriage roads and sow seeds to provide food for the dinner tables of the comfortable classes. The political point—with its attendant implication that thoughts of revolution were never out of the question—would have been clear to the Salon audiences of 1851.

Equally troublesome to the art critics was the representation of peasants and laborers as heroic figures deserving of the same respect as those typically portrayed in history paintings. Nonetheless, Théophile Gautier (1811-1872), one of the leading art critics of the time wrote in La Presse that The Sower was the most powerful representation of peasantry at the Salon, noting that “...he is bony, gaunt and scrawny under his livery of misery, and yet life pours forth from his large hand, and with a superb gesture, he who has nothing, scatters on the earth the bread of the future.”[8]

Gautier was a consistent advocate for Realism and artistic independence: “One is in error, in our opinion, to affect a positive repugnance or rather a positive disdain for purely contemporary figures. We believe, for our part, that there are new effects, unexpected possibilities in the intelligent and honest representation of what we term modernity.”[9] In short, contemporary life in all its permutations was entirely legitimate as a subject for serious art. By the time the Salon closed on March 6, 1851, the Realist painters were acknowledged as important avant-garde contributors to the Parisian cultural environment.

Julien Dupré: Early Years and Education

Twelve days later, a child was born just a few miles away to Pauline Célinie Bouillié (1830-1885) and Jean-Marie-Pierre Dupré (1809-1904). Julien Dupré arrived on March 18, 1851 and was baptized on March 20 at the parish church of Saint-Jean-Saint-François.[10] The family included a half-brother, Jean-Marie-Pierre, who was sixteen years old when Julien was born.[11] In 1852, Pauline gave birth to a second child, Julie.

The Dupré family lived at the 11, rue des Enfants Rouges in the Marais quarter of Paris, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city.[12] In Dupré’s time, it was a place of stark contrasts. Elegant eighteenth-century townhouses opened onto filth-laden medieval lanes. The extraordinary Place des Vosges, built by Henri IV between 1605 and 1612, was less than a mile from the ruins of the Bastille where the French Revolution had been ignited. In the post-Napoleonic era, the streets of the Marais were crowded with rural laborers seeking work in the factories of industrial Paris, creating a demand for housing that led to increasingly crowded conditions. The Dupré home was located near the medieval complex built by the Knights Templar, who received the property from Louis VII in 1137. The Templars’ first task was to drain the swampy area—le marais—before beginning the construction of their monastery. Over the next six centuries, the site underwent several transformations, including the development of the baroque Hôtel de Soubise beginning in 1708; today the building and courtyard comprise the Musée des Archives Nationales. As a child, Julien Dupré would have seen these large and elegant structures as well as the overcrowded conditions of the poor every day.

Dupré’s father Jean worked as a jeweler, creating both fine jewelry and costume jewelry.[13] His older brother Jean also became a jeweler, and both his sister Julie and his niece Jeanne Henriette married jewelers.[14] Julien was the only child who did not follow this career. Instead, he was apprenticed to a lace-maker in the late 1860s. There, he would have learned to trace patterns and perhaps create simple designs. The advent of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, however, forced the lacemaker’s shop to close and Dupré soon found himself a soldier.[15]

After the cessation of overt hostilities with Prussia and the subsequent civil war of the Commune, Julien Dupré began his formal study of art. In 1872, he enrolled in a sketching class taught by Monsieur Laporte at the École des arts décoratifs in preparation for applying to the École des Beaux-Arts.[16] Once he was accepted, he entered the studio of Isidore Pils (1813-1875) and after Pils’ death in 1875, the studio of Henri Lehman (1814-1882). It was also there that he met Georges Laugée (1853-1937), who would become a lifelong friend.

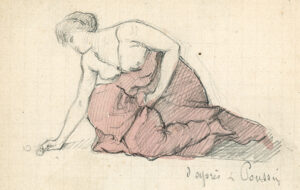

fig. 3. Etude d’après Poussin, Pencil and watercolor, 1873, image courtesy of Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York

One of Dupré’s early sketchbooks reveals the traditional course of study at the École des Beaux-Arts; it is filled with figures and animals as well as preliminary ideas for compositions, and drawings based on paintings by French baroque masters such as Laurent de La Hyre (1606-1656) and Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665). In his drawing after Poussin’s Triumph of Flora (1627), Dupré has chosen to examine the figure of the water nymph Clytie, who anchors the right foreground of the painting. (figs. 3, 4) On bended knee, she reaches for the fragrant heliotrope in the grass, a flower that will become symbolic of her transformation as a result of her unrequited love for the sun god Helios.[17] From Dupré’s perspective, this figure offered him an opportunity to study Poussin’s technique of representing both the human figure and the complex folds of drapery created by Clytie as she leans forward to grasp the flower.

fig. 4. Nicolas Poussin, The Triumph of Flora, 1627. Louvre, Paris

Dupré’s art education at the École was supplemented by study with the academic painter and muralist Désiré François Laugée (1823-1896), the father of his friend Georges Laugée. The Laugée family was based in Nauroy, near Saint-Quentin in Picardy, where Dupré probably first met them on a visit with Georges. By the mid-1870s, however, the two young men were painting side by side while Dupré also studied with the elder Laugée. Like the younger artists, Désiré Laugée had attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and by the 1870s, had a well established Salon career as a painter of religious subjects and portraits; he was also a prolific muralist, implementing large decorative programs for at least four churches.[18] By the time that Dupré met him, D. Laugée had also begun to depict scenes of the countryside surrounding his home, albeit with a degree of formality and elegance that belies the nature of rural life. He undoubtedly encouraged his students to explore the emerging naturalist trend among artists such as Jules Breton and Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose work focused primarily on rural scenes of ordinary people.

By 1875, Dupré made two particularly significant decisions: he prepared for his Salon debut and he proposed marriage to Marie Eléonore Françoise Laugée (1851-1937), Georges’ sister. Like her siblings, Marie was educated as an artist in her father’s studio where she worked alongside the other young painters. Her knowledge of the art world comes through clearly in her letter of April 4, 1876 to her aunt and uncle, Joachim and Caroline Malézieux. The letter begins with an invitation to her upcoming marriage but quickly moves on to discuss her fiancé’s imminent Salon debut.

If you have seen my aunt Nininne recently, you must know how successful Julien's painting was when it arrived here. More than forty people came to see it and everyone liked it very much, starting with the artists who were very happy with it. In short, it was a real and complete success since, the day after his [Dupré’s] return, he found a collector who paid 3500ff for his painting. It was Mister Gallay, a friend of papa, who bought it and he is delighted with its acquisition; you understand that we are no less so than him; it’s such a great start for a first-year exhibitor. The day before yesterday, we learned that the painting received a good placement number. We can therefore now hope for a good place at the Salon where, undoubtedly, it will be noticed.[19]

Dupré’s account books confirm this report in his first entry, which reads "La Moisson en Picardie, (Harvest in Picardy) vendu à M. Gallay. 3500ff."[20] Not quite a month later, the painting appeared at the annual Salon, which opened on May 1, 1876.

On May 17, 1876 Julien Dupré married Marie Laugée in Paris. They lived with the bride’s family both in Nauroy and at their home in Passy near the Bois de Boulogne in Paris.[21] The following spring Marie gave birth to their first child, Thérèse Marthe Françoise, on March 19, 1877. The new father wrote a short, but excited note to his aunt and uncle Malézieux announcing his daughter’s arrival.

“I’m happy to send you an announcement of the birth of our daughter Thérèse; she is a beautiful girl I assure you. My beloved Marie is resting now, but she had a hard time. She asks me to give you a hug; little Thérèse also sends you kisses. Excuse the brevity of this letter but I am a little overcome with emotion. Hug my cousins for me. I embrace you with all my heart.”[22]

Launching a Career

Dupré’s successful Salon debut in 1876 marked the beginning of a distinguished career. In May 1877, his work was again accepted by the Salon jury, and Fauchers de Seigle, en Picardie (Rye Reapers in Picardy) was subsequently sold to a Mr. Wadsworth of New York for 2500ff. Another canvas, Moissoneurs Buvant (Harvesters Drinking), was sold to a Mr. Turquet that year for 1000ff, bringing his total income to 3500ff for the year. While not a fortune, this was a comfortable income for a twenty-six-year old artist.[23] It was sufficient to establish a studio at 14 boulevard Flandrin with his friend and brother-in-law Georges Laugée in 1878; the two men would share this studio for many years. (fig. 5)

fig. 5. Dupré’s studio, 14 boulevard Flandrin, Paris

Another indication of Dupré’s growing reputation was the coverage he received in the Gazette-des-Beaux-arts, one of the most prestigious of the Parisian art publications of the time. In his review of the Salon of 1878, Roger Ballu wrote: "The Lieurs de Gerbes [Binding the Sheaves] by Mr. Julien Dupré is distinguished by natural attitudes and an excellent depth of color; there is perhaps a little monotony in the parallel movement of the two figures in the foreground…but one must recognize this robust and serious elevated art."[24] Shortly thereafter, the painting was purchased by the French government. In addition, the well respected publishing house, A. Cadart Éditeur-Imprimeur, produced an etching of this painting for inclusion in an annual Salon album.

The following year, Dupré received his first Salon jury recognition, an honorable mention for Glaneuses (Gleaners). The year 1879 was also marked by a dramatic increase in sales, including the painter’s first forays into the international market via the Knoedler Gallery, New York and Arthur Tooth & Sons, London.[25] In Paris, Dupré’s 1879 Salon painting La récolte des foins, Le regain (Second Harvest) was purchased by Goupil & Cie where Théo van Gogh would soon take the reins as managing director.[26] His sales for 1879 totaled 9750ff, nearly tripling his income from two years earlier and allowing him to provide a comfortable life for his growing family.[27] In the four years since his Salon debut, Dupré established his reputation as a notable young painter who positioned his work within the Realist frame of reference established by the generation of the 1830s.

Notes:

[1] Letter 292, Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo van Gogh, The Hague, Sunday, 10 December 1882. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. no. b264V/1962.

[2] Julien Dupré’s submissions for the Salons of 1881 and 1882 attracted press coverage and may have been reproduced either as prints or photomechanical images which van Gogh could have seen in The Hague. Two paintings were shown at the Salon of 1881, La Récolte des Foins (#813) and Dans la Prairie (#814). In 1882, his entry was Au Pâturage (#939).

[3] Of particular note were the artists who gathered near the village of Tervueren, Belgium beginning in the 1850s. Like the Barbizon painters, their intent was to capture an image of the natural environment without altering it to conform to an academic formula. This group was closely allied with the Brussels-based Realist group associated with the Atelier Libre Saint-Luc that began in 1846. See Janet Whitmore, “Building a Cultural Identity: Belgian Realists and the School of Tervueren” in Toward a New 19th-Century Art, Selections from the Radichel Collection (Minnetonka, MN: Books & Projects, 2017) 66-79.

[4] Gabriel P. Weisberg and Petra T. D. Chu, eds., The Popularization of Images, Visual Culture Under the July Monarchy (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[5] Gabriel Laviron and B. Galbacio, Le Salon de 1833 (Paris: Librairie Abel Ledou, 1833) 25-26. Available at the Hathi Trust site at: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433082151287&view=1up&seq=33 See also Gabriel P. Weisberg, The Realist Tradition, French Painting and Drawing 1830-1900 (Cleveland: The Cleveland Museum of Art in association with Indiana University Press, 1980) 1-21. [L’art ne consiste pas à faire des trompe-l’oeil, mais bien à rendre le caractère particulier de chaque chose que l’on veut représenter. Pour cela il faut voir et comprendre, c’est-à-dire qu’il faut avoir l’âme assez puissante pour saisir les différences caractéristiques qui sont dans la nature, et, ce qui peut-être est encore plus rare, l’audace de les rendre dans toute leur vérité.]

[6] The Brasserie Andler was located in the Latin Quarter near the intersection of what is now the Boulevard Saint-Germain and the rue Hautefeuille. According to the January 1889 issue of Harper’s Magazine, “It was there that the Parisians first learnt to drink beer; for forty years ago it must be remembered, the Parisians went to the café to drink coffee: beer was then regarded as a strange drink, almost a gastronomic curiosity.” See Theodore Child, “Characteristic Parisian Cafés”, Harper’s Magazine (1888-1889) Volume 78: 687-703. p. 696. It should be noted that Courbet lived on the rue Hautefeuille, not far from the brasserie. See Sarah Faunce and Linda Nochlin, Courbet Reconsidered, (New Haven, NJ: Yale University Press and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1988) 83. Exhibition Catalogue.

[7] Percy B. St. John, The French Revolution of 1848: The Three Days of February, 1848, (New York, 1848) 72-84. It can be viewed online at Fordham University’s Modern History Sourcebook: Percy B. St. John: The French Revolution in 1848 at https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1848johnson.asp

[8] Théophile Gautier, “Salon de 1850-51”, La Presse, 15 March 1851. Cited in Lynette Stocks “Théophile Gautier: Advocate of “Art for Art’s Sake” or champion of Realism?” in French History and Civilization, vol. 2, August 28, 2017: 41-60. See https://h-france.net/rude/vol2/stocks2/ See also Stocks, Théophile Gautier Critique Liberté, Fraternité et Défense du Réalisme (Paris: Seguier, 2011).

[9] Théophile Gautier, Salon de 1852, La Presse, 27 May 1852. Cited in Stocks, 58.

[10] The church of Saint-Jean-Saint-François, located at 13 rue du Perche in the Marais district of Paris, was renamed Sainte-Croix des Arméniens in 1970.

[11] Jean’s mother was Irma Marie Madeleine Françoise Bouillié, who died in 1849. His father then married his sister-in-law Pauline in 1850.

[12] Félix Lazare and Louis Lazare, Dictionnaire administratif et historique des Rues de Paris et de ses Monuments (Paris: 1855) 197. The rue des Enfants Rouges no longer exists, but has been incorporated into the rue des Archives in 1874.

[13] Atelier de feu, Julien Dupre, 1851-1910, (Paris: Galerie des Artistes Modernes, 1911.) n.p. Exhibition catalogue.

[14] For the Dupré family genealogy, see: http://www.peintres-et-sculpteurs.com/arbre-genealogique-317-dupre-jean-marie-pierre.html

[15] He was listed in the military census from 1871-1873, Number 263. At that time, his parents’ address on the rue des Enfants Rouges was still listed as his residence.

[16] The École des Beaux-Arts is today known as the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts (ENSBA), a change which reflects its role in the centralized educational system in France. This publication uses the name that existed during the period of Julien Dupré’s life.

[17] For a discussion of the iconography of Poussin’s painting, see Thomas Worthen, “Poussin’s Paintings of Flora”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 61, No. 4 (December 1979): 575-588. According to Worthen, Poussin’s inclusion of Clytie most likely has its origins in Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

[18] Désiré Laugée’s mural paintings can be seen at Saint Pierre du Gros Caillou, the Church of Sainte Clotilde, and at Sainte Trinité in Paris as well as at the Basilica of Saint-Quentin near his home in Nauroy. He began exhibiting at the Salon in 1845.

[19] Letter from Marie Eléonore Françoise Laugée to Caroline and Joachim Malézieux, 4 avril 1876. Collection of Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York. [Si vous avez vu ma tante Nininne depuis peu, vous avez dû savoir le succès qu’a obtenu le tableau de Julien à son arrivée ici, plus de quarante personnes sont venues le voir et tout le monde l’a beaucoup aimé, à commencer par les artistes qui en ont été très contents. Enfin, cela a été un vrai succès et un succès complet puisque, le surlendemain même de son retour, il a eu la chance de trouver un amateur qui a payé son tableau 3500 Francs. C’est Monsieur Gallay, un ami de papa, qui l’a acheté et il est enchanté de son acquisition ; vous pensez que nous ne le sommes pas moins que lui ; c’est un si beau début pour un exposant de première année. Avant-hier, nous avons appris que le tableau est reçu avec un bon numéro de placement. Nous pourrons donc espérer maintenant une bonne place au Salon où, assurément, il sera remarqué.]

[20] Julien Dupré account book. Sales for 1876, entry no. 1. Collection of Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York. The painting’s location is currently unknown, but an early oil sketch of it still exists. See Catalogue W1078S.

[21] The Laugée home in Paris was located at boulevard Lannes, 15 bis, an elegant tree-lined street surrounded by large parks in the 16th arrondissement.

[22] Letter from Julien Dupré to Caroline and Joachim Malézieux 19 mars 1877. Collection of Rehs Galleries, Inc., New York. [Cher oncle et chère tante, Je suis heureux de venir vous annoncer la naissance de notre fille Thérèse ; c’est une belle grosse fille, je vous assure. Ma chère Marie se repose maintenant, mais elle a bien souffert. Elle me charge de vous embrasser ; la petite Thérèse vous envoie aussi des baisers. Excusez ma lettre si courte, mais je suis un peu émotionné. Embrassez mes cousines pour moi et mes cousins. Je vous embrasse de tout mon cœur. Votre neveu, Julien Dupré.]

[23] The French franc was tied to the gold standard during Dupré’s working lifetime. To understand the economic values of the time, a bottle of red wine would have cost .5ff. Dupré could have purchased 7000 bottles of wine for his 3500ff.

[24] Roger Ballu, "Le Salon de 1878”, deuxième livraison, Gazette des Beaux-arts, 1 août 1878 (169-195):185. [Les Lieurs de Gerbes de M. Julien Dupré se distinguent par le naturel des attitude et l'excellent coloris des fonds; il y a peut-être un peu de monotie dans le mouvement presque parallèle des deux figures du premier plan; mais, de même que dans la Glaneuse de M. Laugée fils, il faut reconnaître un art sain et des tendence sérieuse et élevées.]

[25] Julien Dupré account book. Sales for 1879, Entries nos. 11, 14, 15 and 20.

[26] Julien Dupré account book. Sales for 1879, Entry no. 10. See also Goupil livre no. 9, Stock No. 13557, Spread 215, row 4 at Getty Research Project, Digital Collections: https://rosettaapp.getty.edu/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE1674514